In this lesson you will learn that the way is the goal.

“Altitude Training”

“Altitude Training”

To make it clear right away: this chapter is unnecessary! Because you don’t extend your range by specific training. Your range expands naturally if you continuously work on your blowing technique. See below how James Morrison tells you basically the same (he is a trumpeter, but his explanations also apply to the alphorn):

Why the chapter might still be necessary: There’s that moment when you want to play the next higher note, but you just can’t. Subjectively you have the feeling that it is due to a lack of strength. You start pushing, squeezing and gagging around it. And maybe at some point the sound will actually come – if only croaking and unreliably. But soon you’re bumping into the ceiling. Your way up is blocked.

The one-sided focus on strength (“altitude training”) harbors two fundamental problems:

- The overall system gets out of balance. As you learned in chapter 4, the pitch is determined by the interaction of tongue and lips. This overall system requires not only strength but – above all – dexterity (fine motor skills). You can tense your lips as much as you want… – as long as you don’t manage to position them correctly and make them vibrate with a sufficiently fast air flow, no sound will be produced! Your overall system is only as good as its weakest element.

- You are training the wrong muscles. As long as your fine motor skills around the lips don’t know how to create tension in the right place, they will use the wrong muscles. For example, when you press your mouthpiece to your lips, you are training your forearms instead of your lip muscles. Bottom line: your focus on strength is keeping you from building strength where you actually need it. It’s a bit like someone who puts too much weight on the machine at the gym, but still doesn’t get biceps because they’re doing the exercise incorrectly.

Instead, the sustainable path to altitude is based on continuous improvement of the overall system:

- Improve your base (posture and breathing) so that you have a stable and voluminous airflow. To do this, play with plenty of dynamics and long, clear tones.

- Improve control of your tongue so that it can channel and accelerate the flow of air with precision. Work on efficiency and precision through tying, articulation exercises, and practicing new pieces and complex sequences of notes. Perhaps take up the didgeridoo or learn circular breathing and how to sing into your alphorn while playing.

- Improve your embouchure so your lips effectively regulate their tension and vibrate. Refine your fine motor skills through ongoing control. Develop your lip muscles by buzzing and consistently avoiding pressing. Increase your endurance by playing in mid to high registers, supplemented at best with targeted lip body building.

- Improve your flexibility to keep your overall system working dynamically. Practice rapid changes in pitch and timbre,

The next higher note will sound “by itself” as soon as the overall system is ready for it. By taking the goal out of focus, you move forward on the path. Yes, yes, ok, but how long does it take? There are no reliable statistics on this from the Federal Yodelers Association. My estimate: beginners need on average about 400-500 hours of concentrated practice time (i.e. 2-3 years) until they can play more or less stably up to G5; up to C6 it takes on average 3’000 hours (i.e. about 10 years). However, the dispersion around this mean value is very large: I know greenhorns who played up to G5 after a few weeks, but also seasoned veterans who still can’t get up after ten years of regular practice. But that’s not so important – range isn’t everything!

Experiment. Blaise Bowman suggested the following hack for extending your range: First you need to prepare the body by exposing it to uncomfortable cold. Go outside in the snow wearing only your underwear (provided there is snow), in a freezer room, under a cold shower or – ideally – jump in an icy mountain lake. Play there for 5-10 minutes in the upper register but not quite at the limit of your range (only use the mouthpiece if you chose the cold shower method). Then return to the warmth and give yourself a moment to stop shivering. Now play as high up as you can. What do you notice? According to Bowmann, you can gain half an octave in just a few minutes using this method. I wasn’t able to fully reproduce this result in my self-experiment, but I can at least confirm that the high tones actually come out easier in the defrosting phase.

Support

Support

You may have heard this before, “Beginners play the high notes with lip pressure, professionals with breath support.” This is not absolutely true, of course, but contains a kernel of truth. In your overall system, a stable and voluminous airflow is at the very beginning. If you now want to bring the overall system to high performance when playing at altitude, your everyday breathing is no longer sufficient to produce the necessary air flow – you need support.

By “support” is meant the activation of various accessory muscles in the area of the diaphragm. While your normal exhalation happens through the (passive) relaxation of the diaphragm and muscles in the chest area, your auxiliary muscles make an active contribution to the guided exhalation. When you activate breath support, you enhance your base for clarity of tone, agile dynamics, endurance, and range. This is how you can develop a body feeling for the support:

- Cough. The large back muscle (musculus latissimus dorsi, also known as “cough muscle”) and the psoas muscle (musculus quadratus lumborum) play a central role in the support. Both are also activated when coughing. You can feel these muscles by cupping your hands (your thumbs on your lower back) and coughing.

- Push air. Instead of coughing, you can also actively squeeze air, for example by impulsively saying “tsssss” or blowing up a tight balloon. Try both with and without support. Again check the muskels of your flanks and lower back with your hands.

- Play on one leg. When your body struggles with its balance, it automatically activates the muscles involved in support. Playing on one leg is a good trick if you’re having trouble activating breath support.

Blow-out exercises are sometimes recommended to strengthen blowing power. I don’t think you need such accessory muscle body building on the alphorn; however, the practice can help you get a feeling for the support. You can achieve the same effect with conscious, rhythmic “Breath Attack” (e.g. exercise #2.7&2.8 of the workout for alphorn and buechel).This systematic activation of the support is central to air flow and sound culture. Especially in the high register you should always check whether your auxiliary muscles are supporting you enough. If your alphorn sounds unsteady when played high or loud, it may be due to the lack of support. By systematically activating your breath support, the muscles involved develop on their own.

![]() Further information

Further information

- Youtube presentation by Alexandra Türk-Espitalier. Her team at Vienna University of Music and Performing Arts did a clinical study on the effectiveness of breath training. She found that while musicians can strengthen their breathing muscles with specific devices, they are not able to translate this additional power into range or endurance on brass instrument. Conclusion: breath gyms are a wast of time.

Climax

Climax

One could go on and on about the connection between pitch, steeples, cannons and male fantasies. The fact remains that high notes are associated with climaxes in our culture, and this phallic aesthetic is also common in alphorn music. Be it in the interpretation or hard-coded in the score, we often encounter a clear crescendo when the melodies climb in the high registers. As an example see below the beginning of the piece “Am Brienzersee” by Ulrich Mosimann (notated by Alfred Leonz Gassmann); here an intensification of the opening motive leads directly into a fortissimo at G5.

On the alphorn you have to decide how to deal with this cultural expectation. Two grains of salt:

- This dynamic hardly corresponds to the historical performance practice of the old mountain shepards. Rather, it was introduced to the alphorn in the 19th century by professional trumpeters (the first professional alphorn teacher, Ferdinand Fürchtegott Huber, had previously worked as a trumpeter in an opera).

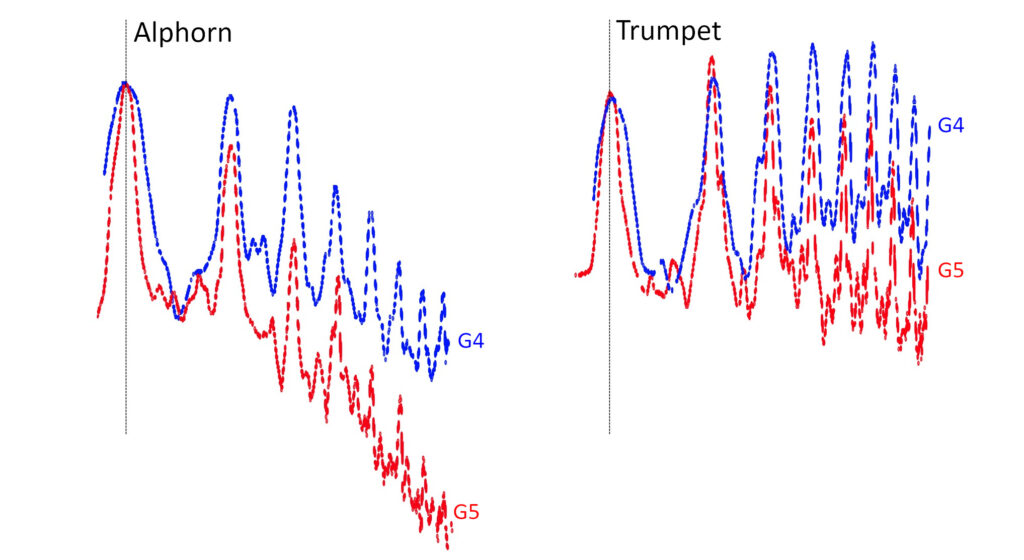

- The alphorn has a completely different sound than the trumpet. Unlike the trumpet, the alphorn loses overtones in the high register. You can see this in the graphic below by comparing the spectrum of G4 and G5. With the trumpet the two notes do not differ fundamentally; both show a relatively flat overtone profile. In contrast, the overtones of the alphorn decay much faster. This effect is even much stronger in G5 where only a few overtones are perceptible. With other words, the alphorn loses sound quality. It is physically impossible to achieve the same effect in the high register as with the trumpet!

The good news: you can free yourself from the climax culture and do exactly the opposite – play fine in the high register and voluminous in the low register. This not only makes your life easier (you save energy), but also achieves a completely different effect. Highlights can also be set by restraint, namely by stopping very briefly before the lyrical, gentle, fine high note sounds.

Trampolin

Trampolin

Objective: light and high

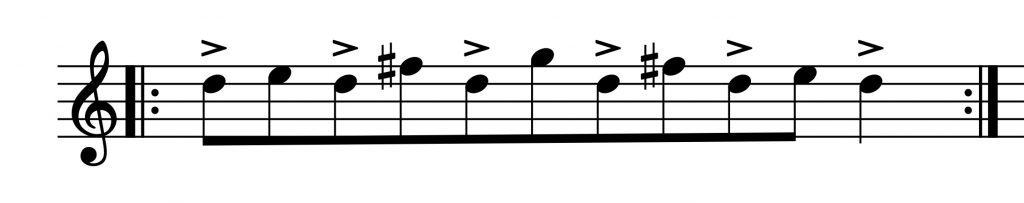

In order to get used to playing high without using any force, you can train specifically with the “trampoline technique”. Again, use any exercise from Workout for Alphorn and Büchel, in particular from the “Interval Training” section (here #4.1 for the range D5 to G5):

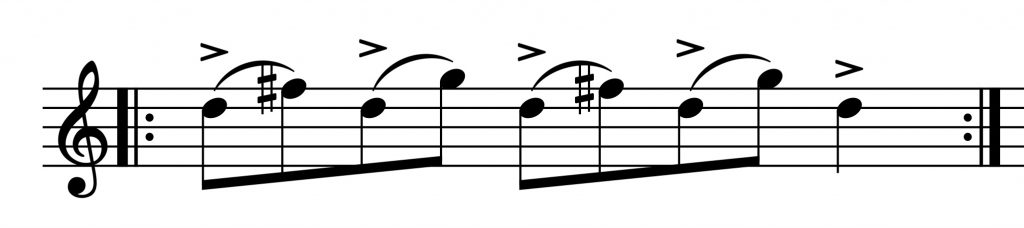

The heart of the exercise are the jumps (up from d2 in the example): Emphasize the accent as if you were jumping with the note onto a trampoline and catapult yourself from there into the upper note. The high notes get their energy from below; like a by-product of the preceding low note. It’s best to play the exercise legato (tied), slowly and precisely in meter. Of course, you can also take out a certain part of it and repeat it in groups:

Also try to incorporate this technique when rehearsing new pieces and listen to the effect.

Train Below The Peak

Train Below The Peak

Objective: Improve your endurance.

Range is also a stamina issue. Sometimes you get very high right after the warm-up, 10 minutes later you’re stuck two notes below that.

Marathon runners will give you the following advice to build up your endurance: train for a long time at a low pulse rate. Applied to the alphorn, this means: train for a long time two notes below your maximum pitch. For example, if you are working on the G5, play intensively in the D5-E5 range for about 10 minutes every other day at the end of your practice session. And just like in a marathon, the rule is: loosen up, don’t press, focus on clean movements.

Of course, you can also incorporate this endurance training into your other practice blocks. E.g. study a piece with appropriate range or try to improvise playing every other note in D5 or E5….).