In this lesson you will delve deeper into the base of a great sound.

Posture

Posture

Perhaps your posture is physiologically suboptimal. Do you work sitting at the computer all day and you are not used to standing for long periods of time? If you get back or neck pain while playing the alphorn, this may be a sign of poor posture. I recommend that you seek competent help by a physiotherapist in this case. Poor posture can often be corrected in a reasonable amount of time with a few targeted daily exercises. Neglected muscles can be trained, shortened muscles can be stretched and tense muscles can be loosened. With this you gain in quality of life, playing the alphorn (standing) is no longer a torture and suddenly your horn sounds much better.

Without slipping into the role of the physiotherapist, here are a few general tips.

- The goal is always: relaxed and yet upright

- Stand with both feet parallel (not pointing in or out) and hip-width apart. Avoid an asymmetrical weight distribution – even when playing in terrain on uneven ground. Try playing barefoot – some musicians manage to have a more stable posture if they connect directly to the ground.

- Place the alphorn at the correct distance from you, i.e. so that the mouthpiece reaches right up to your lips. If you have to bend forward to the mouthpiece, your instrument is too far away.

- Your pelvis plays a central role in posture. Try to get a feel for your pelvis by tilting it down/forward and up from time to time – ideally the axis should be horizontal. If your pelvis tilts downward/forward, try tilting it up toward horizontal; just make sure that your abs stay relaxed as you breathe – you probably won’t be able to do that right away.

- Position your upper body as if you are hugging a large ball (1 meter in diameter). The resulting slight flexion defies the military notion of an upright posture, but maximizes the lung volume you have available for breathing.

- Do not compensate for a weak embouchure with other muscles. Locking your knees or tightening your butt muscles won’t help you get into the high registers.

- Always hold on gently to your alphorn! Cramped hands, arms, pecs and shoulders are definitely bad.

- Move! You can easily rock to the beat or use one hand to support your play with gestures. Alternate between sitting and standing positions.

- Ignore advice from self-proclaimed posture specialists. Postural defects are often symptoms of complex causes. If you push away the symptoms without addressing the cause, you’re will probably make the actual problem worse. When you hear that the real alphorn player has to stand there like a fir tree or a “strong dairyman”, then think of all those players with a hollow back and herniated discs. When they tell you to fill your chests with patriotic pride and shoulders thrown back, think of gasping chest breathing and persistent neck pain.

Breathing

Breathing

A distinction is made between chest and abdominal breathing. With chest breathing, you change the volume of the lungs with the chest muscles by expanding and compressing the chest. If you try fill your lungs with air and then hold your breath, you’re probably mostly using chest breathing. Under stress you also tend to breathe in your chest. We don’t want this stressful breathing when playing the alphorn!

A full and beautiful sound is the result of deep, relaxed breathing. This is “abdominal” or “diaphragm breathing”. In fact, you do not breathe into your belly (you always breathe into your lungs). Rather, your diaphragm moves up and down. When you breathe in, the diaphragm lowers, allowing the lungs to expand. At the same time, the diaphragm pushes out the innards in your abdomen, causing the abdomen to bulge (hence the term “belly breathing”). When you breathe out, the diaphragm arches back up, pushing the air out of your lungs. You straighten up, at the same time the innards take their old place and the stomach becomes flat. Here is an animation of the diaphragm (red) and lungs (pink):

Your breathing usually consists of a mixture of chest and abdominal breathing. So it’s not about stopping chest breathing completely, but about increasing the share of abdominal breathing. If you’re having trouble breathing while playing the alphorn, your chest breathing has probably taken over. Often this happens because of anger or nervousness during your performance. Here’s how to increase your diaphragmatic breathing:

- Sensual inhalation. Sometimes one hears the following advice: “Breathe in, as if you are smelling a bouquet of flowers.” The problem with this is that there are different ways you can smell a bouquet of flowers. If you try to differentiate the fine ethereal vapors with your nose, you are probably sucking the air mainly into your chest. If, on the other hand, you let the beguiling scent of the bouquet of flowers flow into your body with your eyes closed, then the diaphragm takes over as if by itself.

- Focused exhale. If you have difficulties relaxing while inhaling, try to focus instead on the exhalation. As you exhale, imagine a sponge in your stomach, squeeze out every drop, wait two seconds, and then let the air back in. With this trick, abdominal breathing usually succeeds by itself.

- Diaphragm Training. You can also do specific exercises to relax and strengthen the diaphragm muscle. See here for an example.

- Mindful Breathing. Many Eastern relaxation and meditation techniques revolve around breathing into the center of the body. Corresponding practice can be transferred to the alphorn. You can also practice mindful breathing while falling asleep. Perhaps a lesson from Zen will also help you: Don’t breathe, but let the Buddha breathe in you! If you follow this path, your alphorn sounds like a transcendental “ohhhhmmmhhh”.

![]() Further information

Further information

- Here an additional video from the tomograph.

- If you feel that your breathing lacks power, go to the breathing gym. You can find more on this topic in the “breath attack” chapter in Lesson 9.

Dynamics

Dynamics

Objective: You can play with loudness.

In music, dynamics means the variation in loudness. Posture and breathing have an important effect on the dynamics of your tones. Therefore, consciously concentrate on your diaphragm during dynamics exercises.

Here, too, the simplest variant is to vary the dynamics in your daily work with the etudes. Play the same exercise piano once, then forte. Alternate dynamics between two notes or takes. Play crescendo or decrescendo, etc. But be precise – first define the dynamic to be played (e.g. “this part ff, then this part pp”) and then repeat it exactly the same way several times.

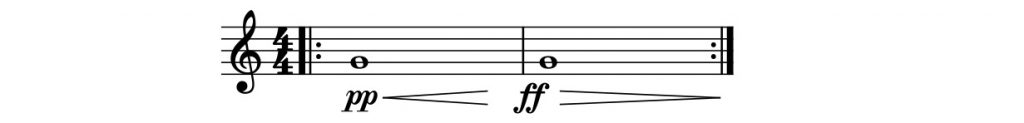

Here is an additional specific exercise. Set the metronome as slowly as possible and pay particular attention to the linear shape of your crescendo and decrescendo (the volume increases continuously over exactly four beats – not, for example, first a rapid increase in volume and then already at the maximum on the third beat). Try this exercise at different pitches for 5-10 minutes daily for 2-3 weeks.

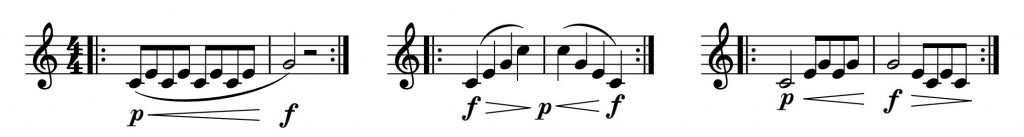

You can also create such exercises yourself by adding a dynamic pattern to short sequences of notes. The point here is not to create particularly original melodies, but to reproduce the dynamics with maximum precision and control. Below are a few ideas; alternatively, you can find a suitable collection of such and similar exercises here.

Finding Sheet Music For Alphorn

Finding Sheet Music For Alphorn

You have been working with etudes since lesson 3. By now, you may be tired of them. If you want to study a few pieces in addition (!) to the exercises, then you may find these free resources to be particularly well suited for beginners: Easy pieces by Hans-Jürg Sommer and the booklet Alphornklänge 2 by Kurt Schmid.

In general, you have three options to get sheet music for alphorn:

- Buy. Unfortunately, as far as I know, there is still no “alphorn songbook”, i.e. a compact collection with the most popular alphorn pieces. Patrick Kissling Cotti’s list or the youtube channel of Alex Zehnder may help you to find good pieces. I also like the publication of the Alphorn Blower Association of Western Switzerland for getting to know various French-speaking composers. Many composers publish their works themselves or you find them at distributors of alphorn sheet music (see here for a comprehensive list). From all the collections, I can recommend the Alphornbüechli by Gassmann (the ultimate classic).

- Freely accessible online. Various composers put their pieces online for free. Many of them use the area on naturtoene.ch, others can be found here. Some composers give away their sheet music on request, via Facebook or a newsletter. You can also find sheet music on the internet that was written for other instruments but can be played on the alphorn, for example here and here for the Trompe de Chasse.

- Sharing. Sheet music is often exchanged or distributed in lessons and workshops as single sheets, pdf-Files or improvised collections. Some of these collections end up in the net (e.g. here or here). Many older compositions are only available in this way today. Some also google for the sheet music of certain pieces and composers and then find them under images. All of this can be more or less legal. However, consider that for some musicians royalties are an essential part of their income and that paying for sheet music is not only fair towards them but also incentivises composers to produce new pieces for alphorn.

In most pieces the first voice goes up to G5. If your range is not sufficient for this, you will have to concentrate on the 2nd voice. As an exercise, that’s perfectly fine. If you want to enrich your experience, you will find practical tips for play-alongs in the next chapter.