Many beginners to alphorn blowing cannot read sheet music. They are usually advised to get an introduction to music theory – as a book, an app or on the internet – and work through it. In fact, a few hours of concentrated self-study are enough to acquire the necessary knowledge. However, due to the limited number of playable notes, not everything taught in music theory can be implemented on the alphorn. Conversely, there are a few peculiarities in the notation of alphorn music that are left out of conventional introductions. For this reason, the wish for a specific introduction for alphorn players is often expressed. Voilà!

Sheet music defines as clearly as possible, in a compact way and understandable in all languages for each note to be played:

Below, we have a look at each of these elements and finish off with a short section on notational conventions related to the arrangement of alphorn music.

Part 1: Rhythm

Rhythm is a central element of (alphorn) music. The alphorn follows the standard notation. Its elements are explained very briefly here. It is important that you not only understand the concepts in principle, but that you can also apply them. You can only achieve this by practising. An excellent collection of rhythm exercises can be found here. I strongly recommend that you do the appropriate exercises after reading the explanations. Especially important are exercises that combine different note values and rests in different time signatures.

Puls / beat

When listening to music, you have probably already unconsciously tapped your foot, nodded your head to the beat, moved your upper body back and forth, danced along or swayed in a group. (Almost) all music has a perceptible pulse: a regular basic beat to which the other musical elements are aligned.

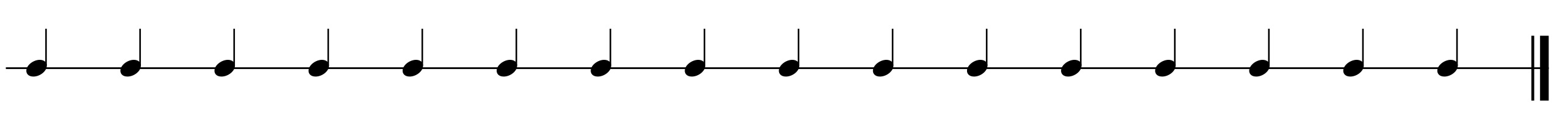

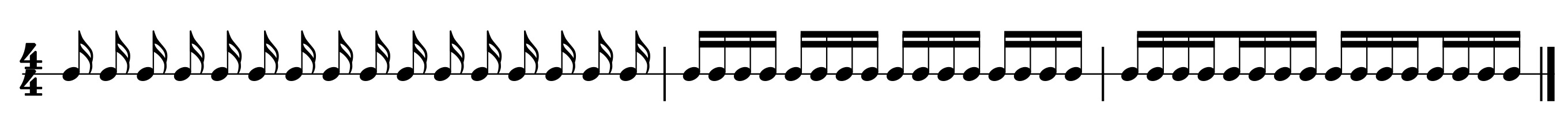

Most of the time (we’ll get to the variations later), this basic beat is notated as a “quarter note”. Below you see 16 quarter notes on a staff. Each quarter note consists of the note head (the black dot) and the note stem (the vertical line pointing upwards from the dot). Sometimes the note is rotated 180° for better presentation – the stem then points downwards; this is purely visual and has no meaning for you when playing. You can imagine the note line as a time axis from left to right, i.e. the 16 quarter notes are played from left to right one after the other:

Bars

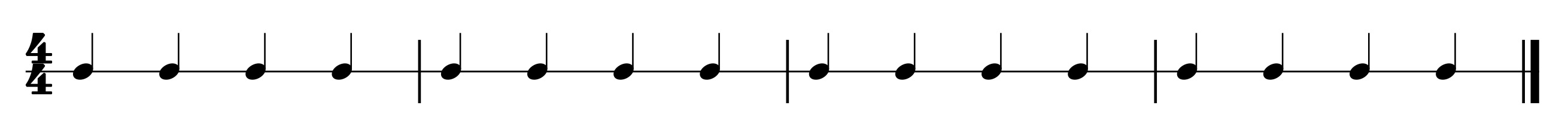

The pulse alone does not create a structure. For this purpose, the individual beats are grouped together. Such a group is called a “bar”. Groups of 4 are most common (variations follow later). Below you can see how the 16 quarter notes have been grouped into four bars of four quarter notes each. Since each bar consists of four quarter notes, such a bar is called a “four-four bar” or “4/4 bar”.

To make the subdivision into bars audible, the first pulse is emphasised. You can also count along with the beat (“one-two-three-four, one-two-three-four …”):

Note values

In addition to quarter notes, there are other note values:

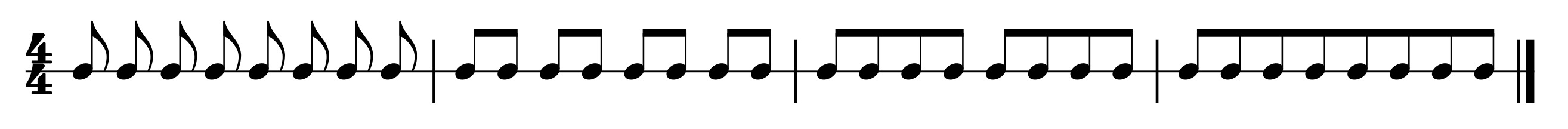

Eighth notes

An eighth note lasts half as long as a quarter note. So there is room for two eighth notes in the space of one pulse. Visually, the eighth note is distinguished from the quarter note by a small “flag” at the stem of the note. For better legibility, eighth notes can also be notated in groups, in which case the flags become bars over the whole group (this has no influence on the way of playing). To make the difference between the pulse (quarter notes) and the notes (eighth notes) audible, I have added a metronome in the setting below. On every second eighth note you hear a percussion wood and on the first pulse of each bar it sounds a little higher:

To learn the note values, some find it helpful to bob one foot to the beat. The tip of the foot hits the floor on each pulse (so far on each quarter note). Eighth notes are played when the tip of the foot touches the floor and also when it makes the opposite movement upwards again. This technique helps to get things in order – but make sure that it does not become a robot movement!

Sixteenth notes

Sixteenth notes are half as long as eighth notes. There are four sixteenth notes per quarter note. Visually, you can recognise the sixteenth notes by the double flag or the double bar:

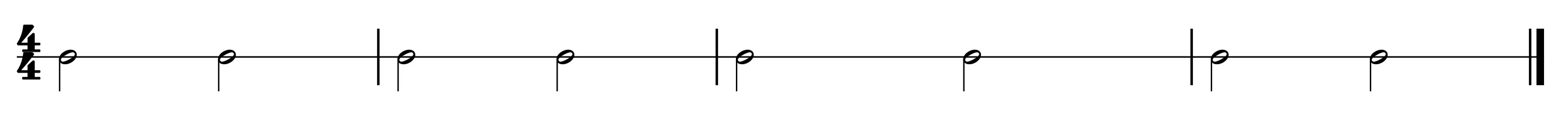

Half notes

Half notes are twice as long as quarter notes. A half note is therefore sustained over two pulse beats. It is notated similarly to the quarter note, but with an empty notehead:

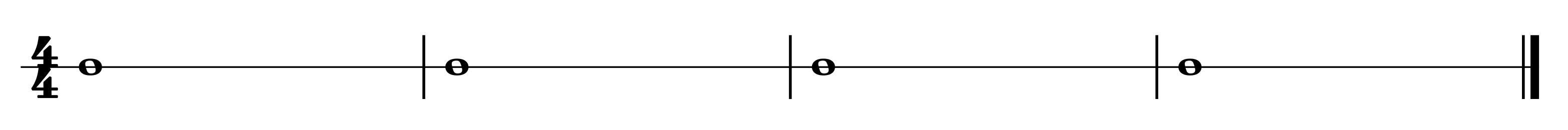

Whole notes

Whole notes are four times as long as quarter notes, so they are sustained over four pulse beats. They are notated as an empty notehead without a stem:

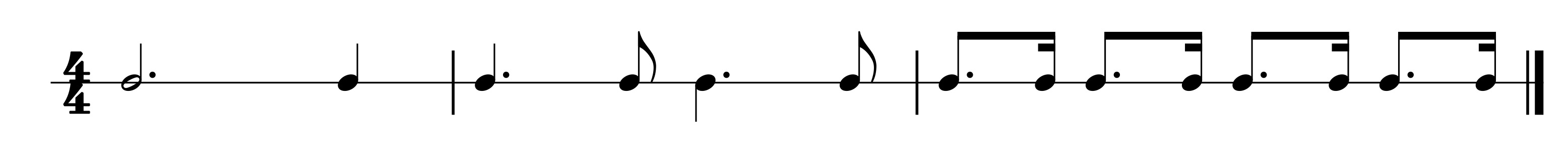

Dotted notes

If there is a dot to the right of the note, it is called a “dotted note”. The dotted note increases the duration of the note by half. A dotted quarter note is therefore the same length as a quarter note plus an eighth note. A dotted eighth note is the same length as an eighth note plus a sixteenth note. And so on:

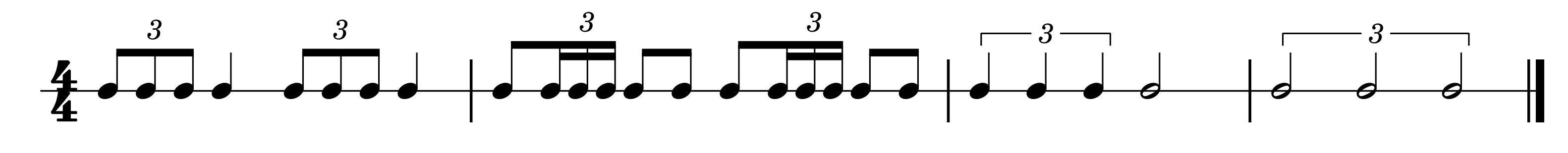

Triplets and n-tiols

In addition to halving and doubling the duration of notes, thirds are also common. With triplets, three notes correspond to the duration of two such notes. They are notated with the number 3 above or below the group of notes. At the beginning of the first bar there is a triplet of eighth notes; it lasts the same as two eighth notes, i.e. a quarter note. So the sixteenth-note triplets in the second bar are the same length as an eighth note. In the third bar, the three quarter notes take the duration of two beats.

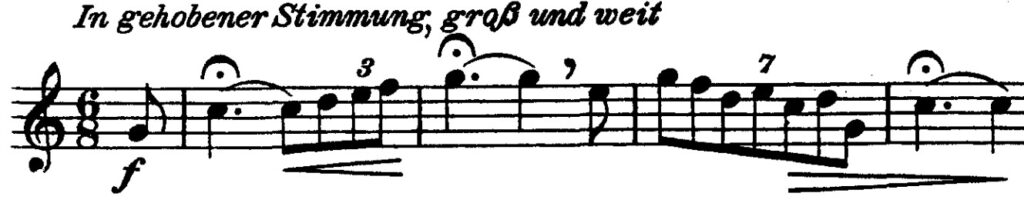

In alphorn music, besides triplets, quintuplets, sextuplets and septuplets also occur. Below as a famous example of Gassmann’s Frutt-Kühreihen. Such n-tiols are usually not played strictly in time; see here for an interpretation of the Frutt-Kühreihen.

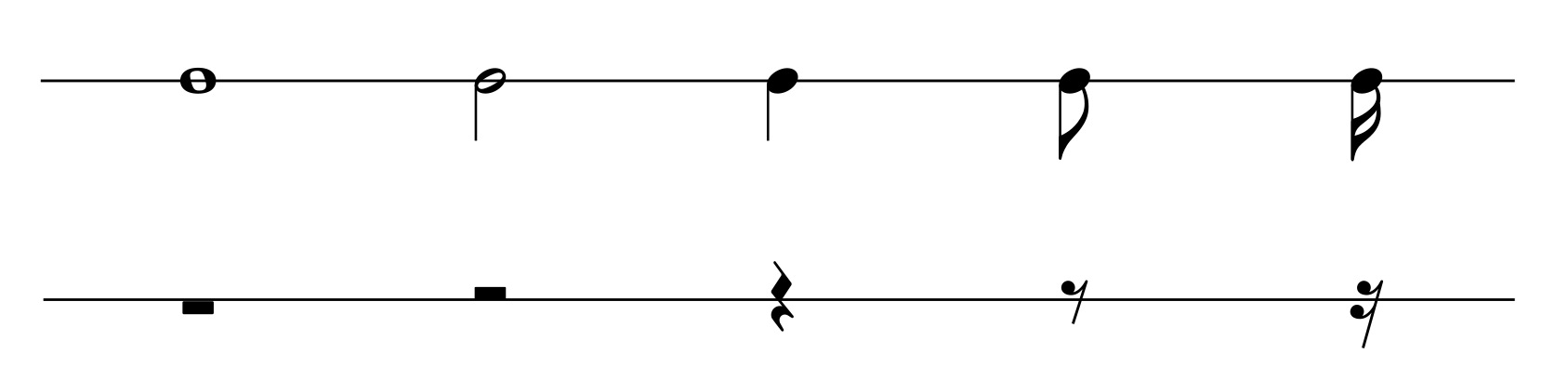

Pauses

For each note value there is a corresponding pause value:

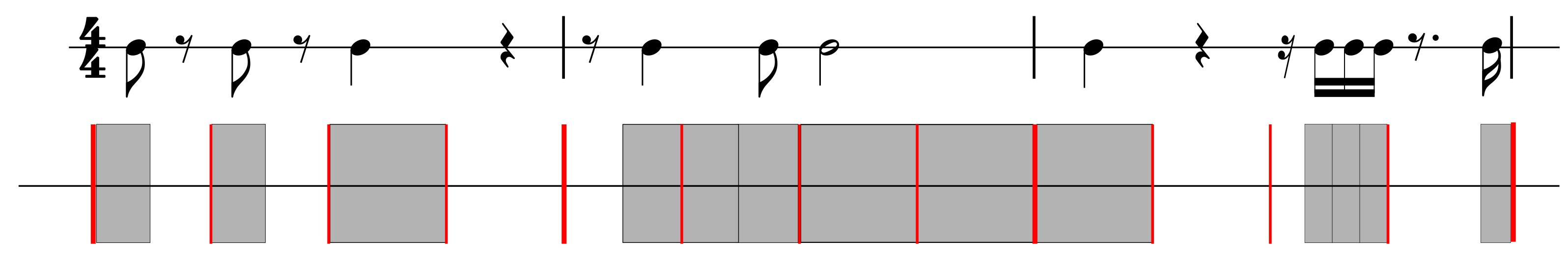

As with the note values, a dotted pause is extended by half. By the way, a pause does not mean that you don’t make music during this time. Silence always has a musical function: you leave space for other voices, you let music reverberate in your head and structure the melody. On the other hand, a pause means that you don’t blow a note for a moment. Below is a short example of the use of pauses. The red lines show you the metronome beats, the grey areas the blown notes. Note that the rests can also fall on the beat (this is sometimes called syncopation). In the second bar, the syncopated quarter note also goes beyond the one beat.

Time signatures

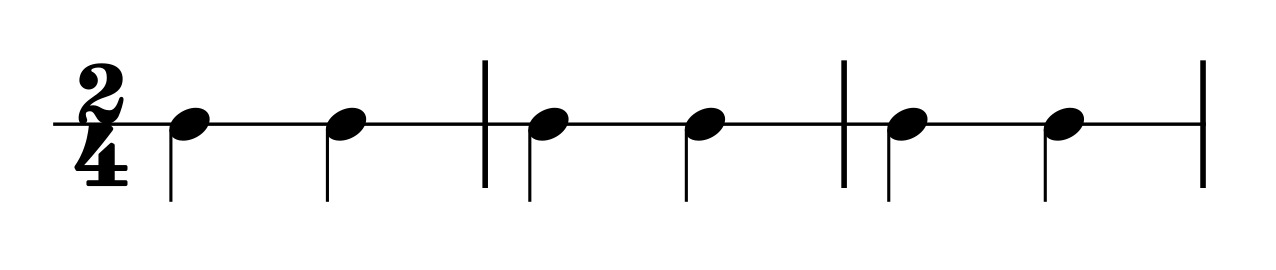

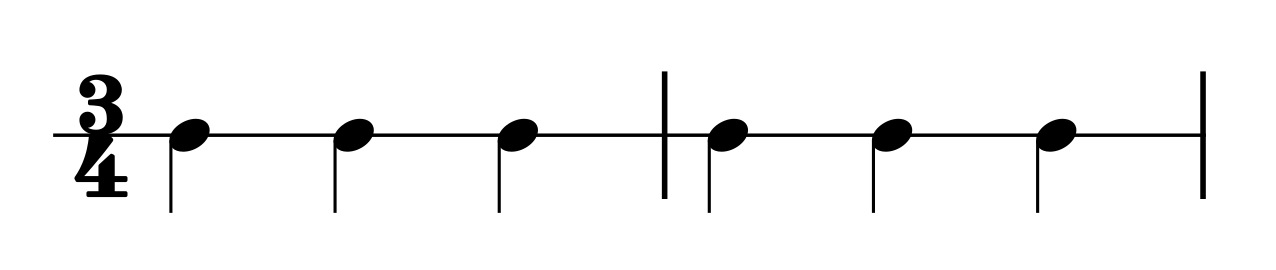

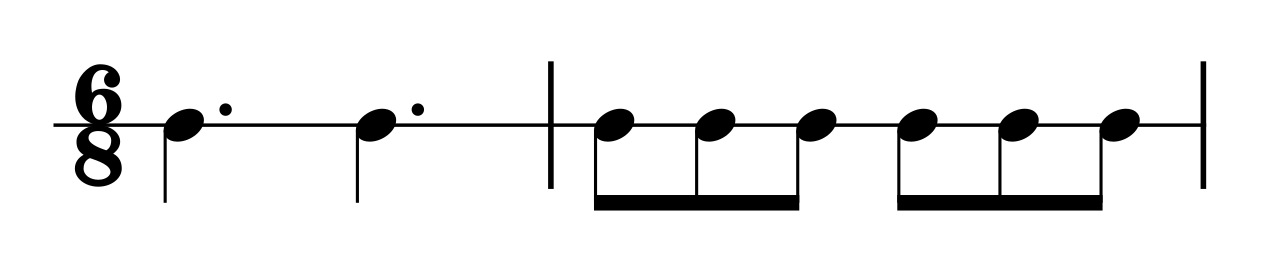

Time signatures have an important influence on the overall impression. You notice this best when you dance to the music. So far we have written all the examples in 4/4 time. Other time signatures with pulse beats on each quarter note are 2/4 time and 3/4 time (“waltz time”; “one-two-three, one-two-three…”):

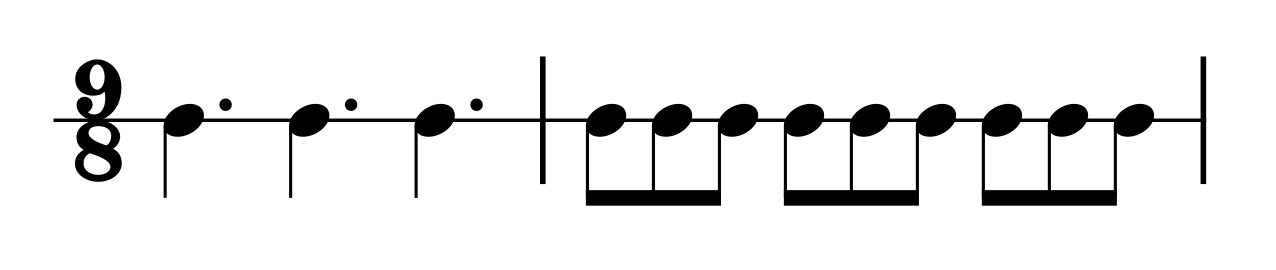

In addition to these “even” rhythms on quarter notes, there are also “ternary rhythms” in which the pulse falls on a group of three eighth notes or a dotted quarter note:

Tempo

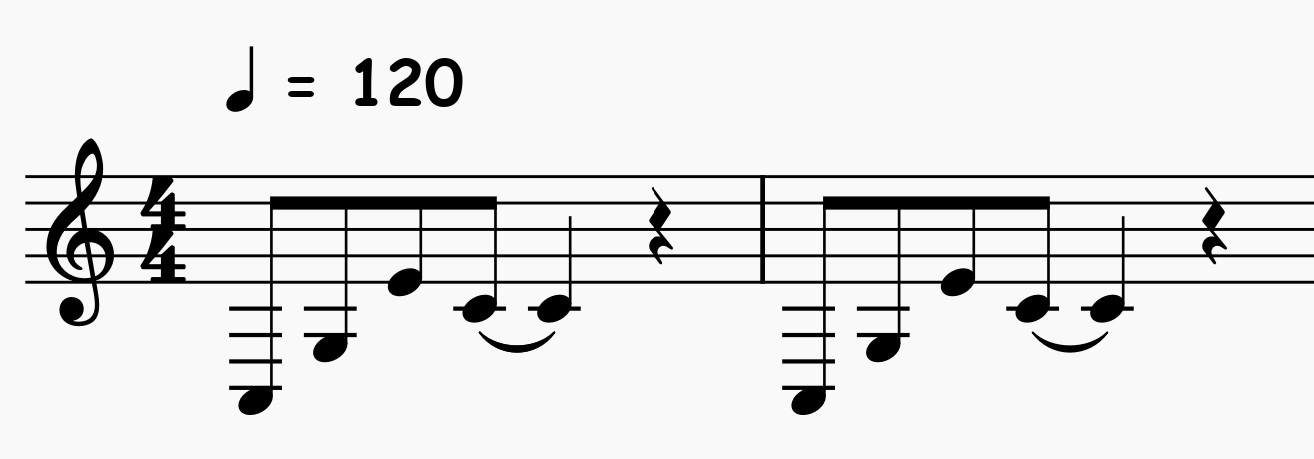

Tempo means speed. In music, it is not measured in miles per hour but in beats per minute (bpm). In even rhythms, the pulse beats correspond to quarter notes, in ternary rhythms to dotted quarter notes. Sometimes such precise indications are found above the first note. Here is an example from the piece Walking by Arkady Shilkloper:

More common (and poetic), however, are Italian instructions. Below is a list of the most common tempo designations. To the right of this is the translation into pulse beats per minute, which is more common in the alphorn literature:

| italian | bpm |

|---|---|

| Largo | 40–60 |

| Larghetto | 60–66 |

| Adagio | 66–76 |

| Andante | 76–108 |

| Moderato | 108–120 |

| Allegro | 120–168 |

| Presto | 168–200 |

In addition to these most common tempi, there are numerous other Italian speed indications (see the corresponding Wikipedia entry). In alphorn music, individual expressions are also added depending on the composer’s imagination (often in German or French). Note also that the translation of Italian terms into bpm is not officially regulated. On your metronomo you may find different values than in the table above. By the way, when practicing with sheet music, it is definitely advisable to use a metronomo. If you don’t have a metronome, you can find many online metronomes (e.g. here) or apps for your mobile phone.

Part 2: Pitch

In the explanations on rhythm in the first part, there was nothing where the alphorn differed from other instruments. With the pitches, however, the alphorn lives in its own world. Without going into details (for a detailed explanation, see lesson 3 of the introductory course): the notes playable on the alphorn differ from the notes of other instruments. Since notation was not developed primarily for the alphorn, this means that notated alphorn music is forced into a corset of notation that is actually inappropriate. In addition, the numerous historical conventions of notation are rather complicated. As an alphorn player, however, you have no choice but to understand at least the elements of this notation that you need to translate strokes and dots into notes.

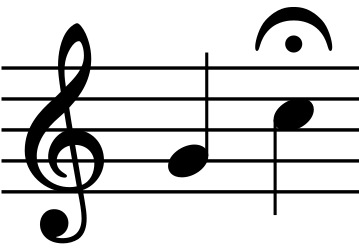

Staff

In Part 1, we lined up the notes on the time axis (=rhythm). With the pitch, a second dimension is added. Below you see an empty staff. The five staves of the staff form the Y-axis. The higher the note in this grid, the higher the pitch. At the beginning of the line there is a new squiggly sign, a “treble clef”. The treble clef serves as a reference for the staff, i.e. a note on a certain staff line has a fixed pitch. There are also other clefs (e.g. the bass clef) where a note on the same staff has a different fixed pitch. With the alphorn, however, you practically always play on a staff with treble clef.

Staves and white piano keys

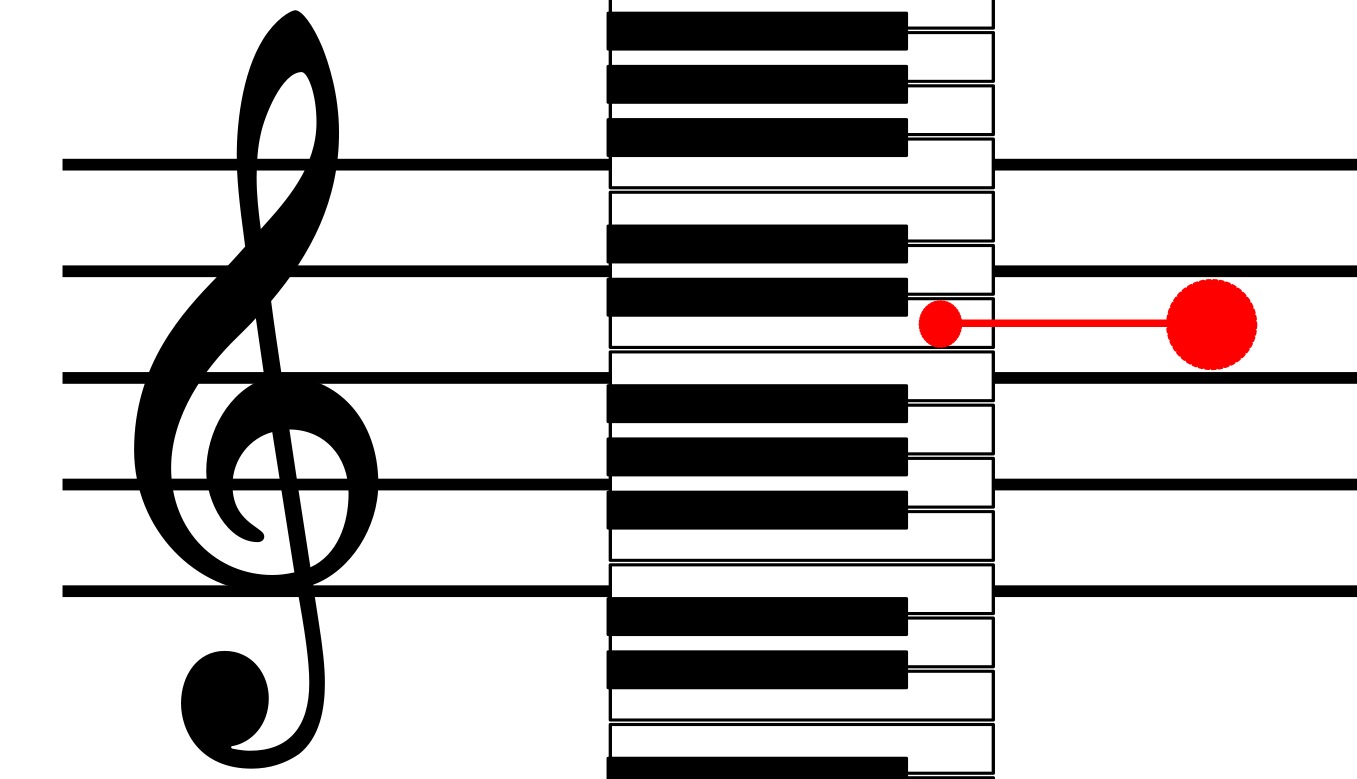

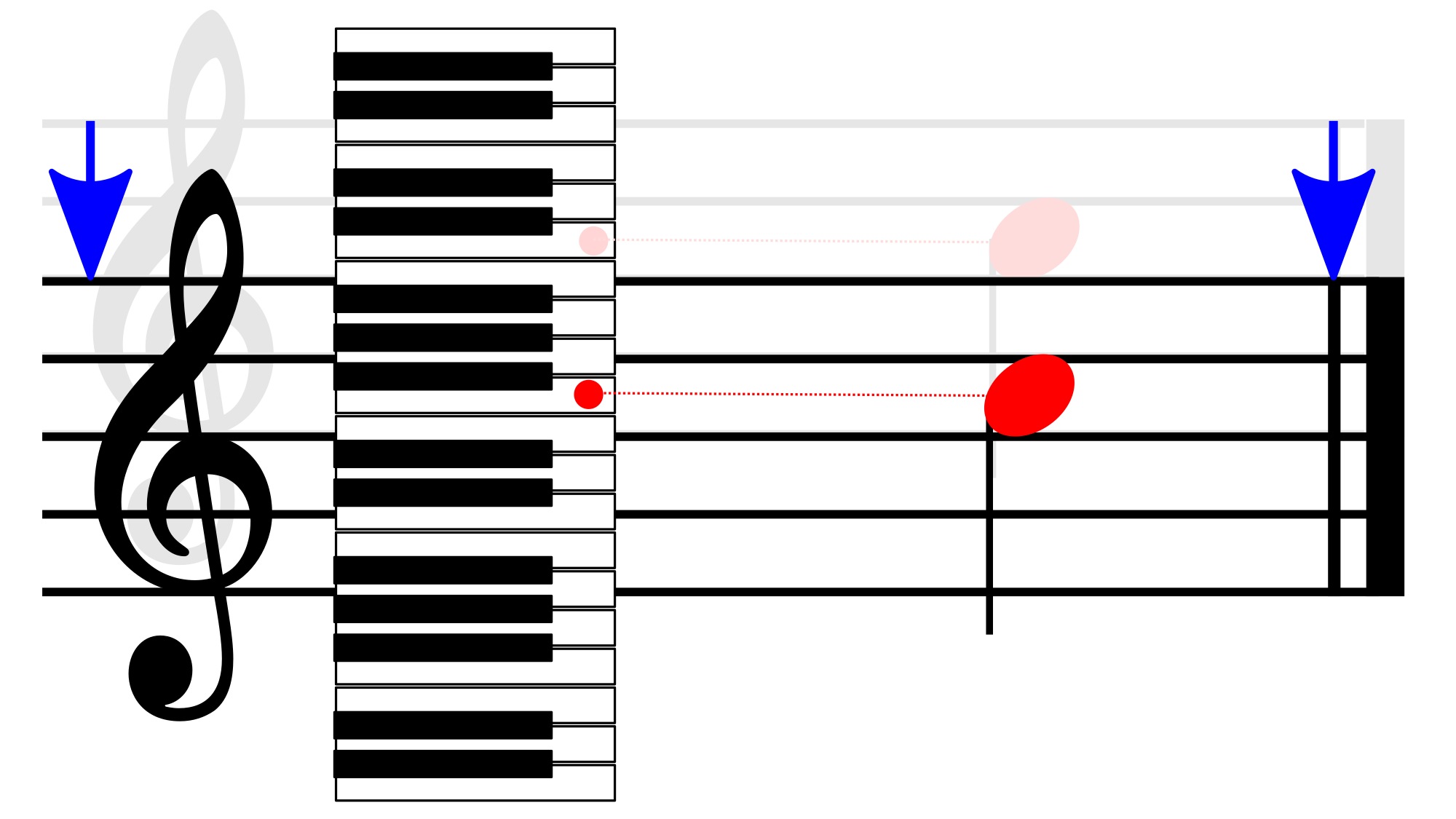

As mentioned at the beginning, the staff is tailored to “standard instruments”. You can see this most clearly on the piano. In the diagram below you can see a piano keyboard rotated by 90°. The white keys lie alternately on a note line or in the space between two note lines. On the piano, the low notes are on the left and the high notes on the right; with the keyboard turned, the pitch rises from the bottom to the top. In red you see a note with the name “C5”. It is located in the space above the middle note line or to the left of a group of two black keys (on a full piano keyboard slightly to the right of the middle).

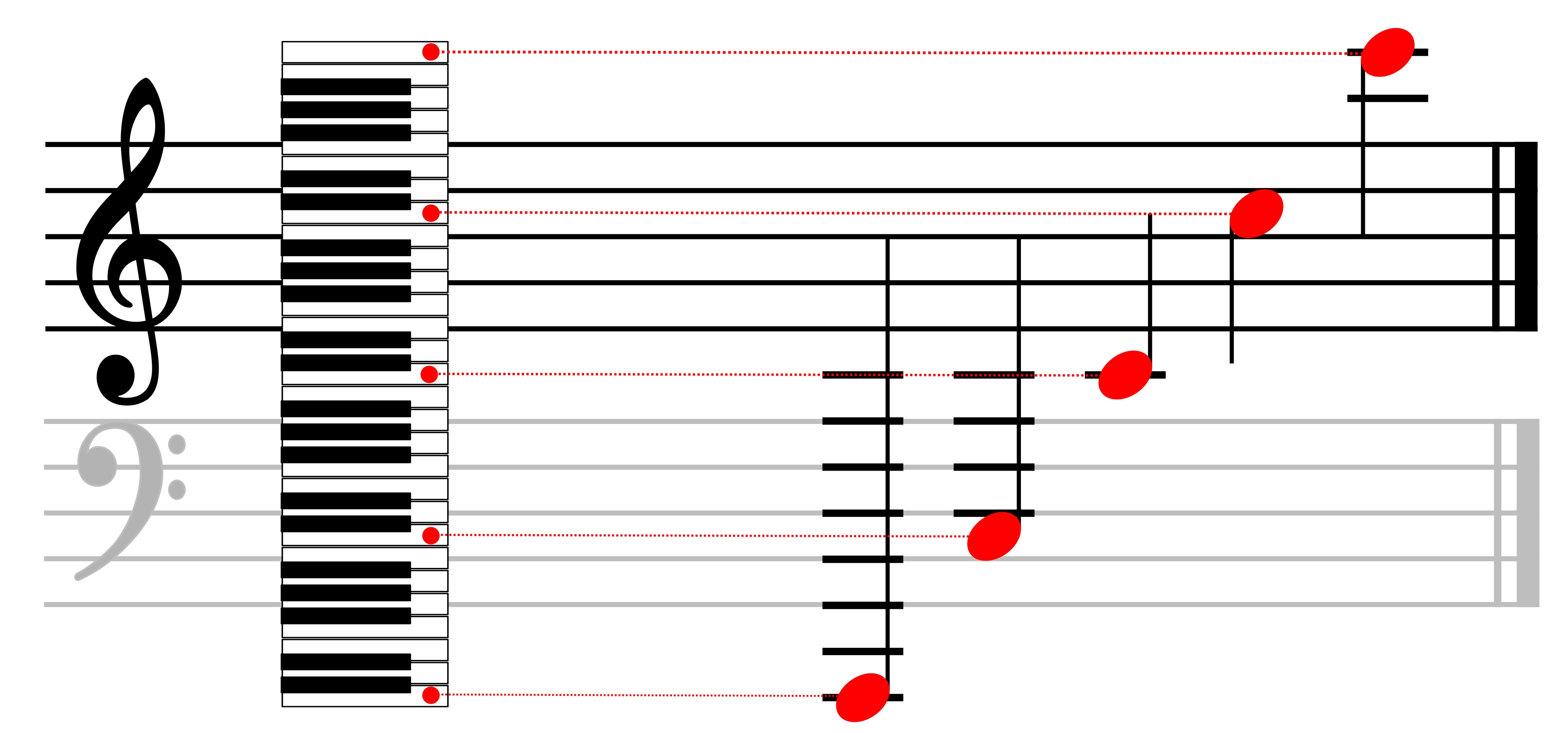

The range of an alphorn goes beyond the limits of the five staves. Therefore, the staff is extended upwards and downwards with auxiliary lines. Below you can see all the notes “C” in the range of an alphorn. The very lowest note (“C2” or also called “pedal tone”) is on the eighth auxiliary line below the staff in treble clef. The auxiliary lines are short horizontal strokes (black) on the stem. Alternatively, the lowest notes could be represented on a staff with bass clef; the pedal tone would then be on the second auxiliary line below the staff with bass clef. The corresponding system is highlighted in grey in the diagram. The highest note (“C6”) lies on the second auxiliary line above the staff with treble clef.

Alphorn sheet music

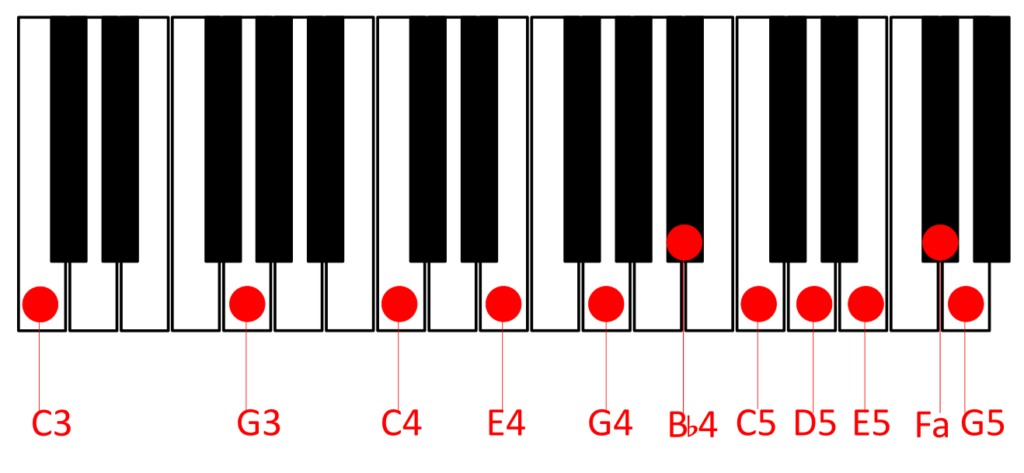

On the alphorn we cannot play all the notes for which there are keys on the piano. Below is a representation with the playable notes. The pedal tone (here notated in bass clef) is practically non-existent in alphorn music. The four top notes require a strong embouchure – only for very advanced alphorn players. The usual range of alphorn music is therefore in the white range.

Below the graphic you will find the appropriate note names. The naming of notes follows certain conventions, with strange exceptions and international language confusion. If you want to learn the details, you can read about it in any standard introduction to music theory. For alphorn players, it is enough to know the names of the notes in your range.

In front of the notes Bb4 and Bb5 you see an “accidental” that ressembles a little “b”. It means that the note is not played on the corresponding white key on the piano, but on the black key a semitone below it (on the keyboard on the left) and sounds a half note “flat”. The note B5 also has a so-called “resolution sign”. This cancels the preceding accidental and turns the note “Bb5” back into the note “B5” without the little b – it is played on the white key again. The fa also has an accidental (a kind of #). It means that the note is played on the black key a semitone above (to the right) and sounds a semitone “sharp”; the corresponding note is called “F5 sharp” on the piano, but in the context of the alphorn it is called “fa” or “alphorn-fa” because of the special tuning. To further confuse us alphorn players, alphorn pieces are sometimes notated without accidentals. Sometimes slightly different accidentals are used to better reflect the tuning of the natural scale. However, all this has no influence on the sound – the playable notes do not change because of a few strokes on the paper.

Below you can see the corresponding piano keys for the usual range C3-G5. Try the tones on a piano; if you don’t have one, here a virtual piano.

The notes C3, C4 and C5 have the same letter in their names. When you play them on the piano, you notice that although they have a different pitch, they sound very similar. In fact, it is “the same note” but shifted by an octave and two octaves respectively. An octave is the tonal space between eight (Latin “octo”) white piano keys. There are other octaves in the usual range: G3-G4-G5 and E4-E5.

The sound of alphorn notes

Alphorns are tuned in F or F sharp. This means that a note played on the alphorn as a “C” sounds like an F or F sharp. The whole scale is therefore shifted downwards by 7 (F horn) or 6 (F-sharp horn) semitones. This parallel shift is called “transposing”. In the diagram below you can see this process for an F horn; the staff slides down in relation to the piano keyboard. The note C5 no longer corresponds to the same key on the piano, but 7 piano keys (7 semitones; counting black and white keys) further down/left – on the key F4. Alternatively, you can also tune the piano down to your alphorn. In the virtual piano linked above, you set the transpose switch to -7 or -6; this makes each note sound lower by the corresponding number of semitones.

In the following table you can hear how the different notes sound on an alphorn in F and F sharp.

Whenever you use a piano or a tuner (app), try to transpose its tuning – otherwise you’ll have to transpose in your head every time! When using a tuner, you will also notice that certain notes – especially Bb4, Fa and Bb5 – deviate greatly on the alphorn. This is not an intonation error, but is due to the fact that the alphorn is a natural tone instrument. For details see lesson 3 of the introductory course.

The same applies to the pitches as to the rhythm: only by practising will you become a master. But luckily, you don’t need to learn all the notes immediately. As a beginner, your range on the alphorn is limited to a few notes anyway. It is therefore sufficient for the time being that you know where your notes lie on the staff. If you work continuously on the exercises, you will internalise the connection between notation and tone in your playing. As your range grows, new notes are added in homeopathic doses. By the time you reach G5, you will have learned the 11 notes of the common range.

Part 3: Qualitative Elements

So far we have distributed tones in a two-dimensional x-y-space: on the time axis and in pitch. This is how the punch card finally defines the music on a barrel organ. Fortunately, with the alphorn we have other qualitative design elements: We can play louder or softer (dynamics) and blow the notes differently (articulation). In your interpretation, you can also vary the timbre of your alphorn, but there is no convention as how to reflect this in sheet music.

Dynamics

In music, “dynamics” refers to the volume. The Italian abbreviations are usually used for this.

| Abbreviation | Pronounciation | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| piano-pianissimo | as quiet as possible |

| pianissimo | very quiet |

| piano | quiet |

| mezzo piano | moderately quiet |

| mezzo forte | moderately loud |

| forte | loud |

| fortissimo | very loud |

| fortissimo forte | as loud as possible |

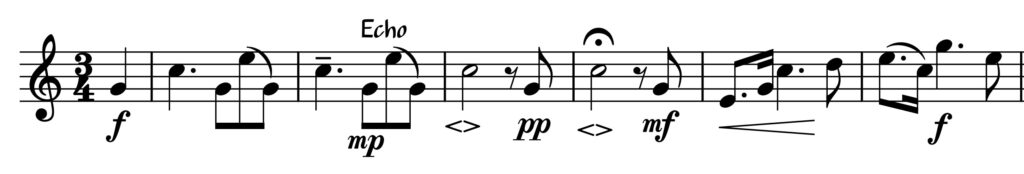

Dynamics are given under the first note from which they apply. See the first line of the piece Alpsegen by Robert Körnli as an example:

Sometimes the dynamics are changed dynamically during the piece. In the example above, you see a scissor opening in the penultimate bar; it shows that the volume increases over this range from the previous mezzo forte to the following forte. Similarly, a closing scissor shows a decreasing dynamic. Instead of the scissors, the abbreviations cresc. (crescendo, increasing in volume) and dim. (diminuendo, decreasing in volume) are sometimes used.

Articulation

Tones can be differently shaped life cycles. You will find more on articulation in lesson 7 of the introductory course. Here we will limit ourselves to the most important notation rules.

Part 4: Arrangement

On a structural level (structure) we can combine several voices and arrange individual parts. Musical notation has certain conventions for these different shaping elements, which you should know.

Repetitions and jumps

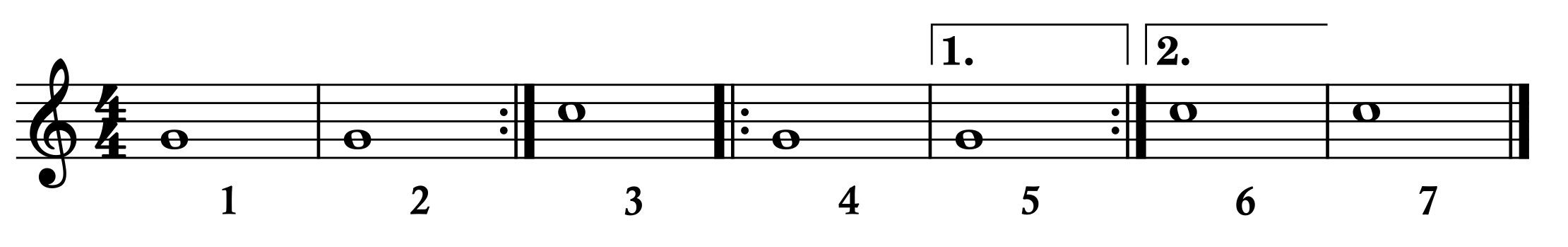

A typical alphorn piece consists of different parts, some of them being played more than once. With repetitions you can save space on the paper. In the example below you see a colon at the end of the second bar. It says that the bars before the colon are played twice. In bar 4, the colon is at the beginning. This forms a repeated section with the next colon. Finally, above bar 5 there is a bar with the number 1. In bar 6 there is the corresponding part 2; on the first pass of the section to be repeated, bar 5 is played, on the second pass from section 6. So in the complete pass you play 1-2-1-2-3-4-5-4-6-7.

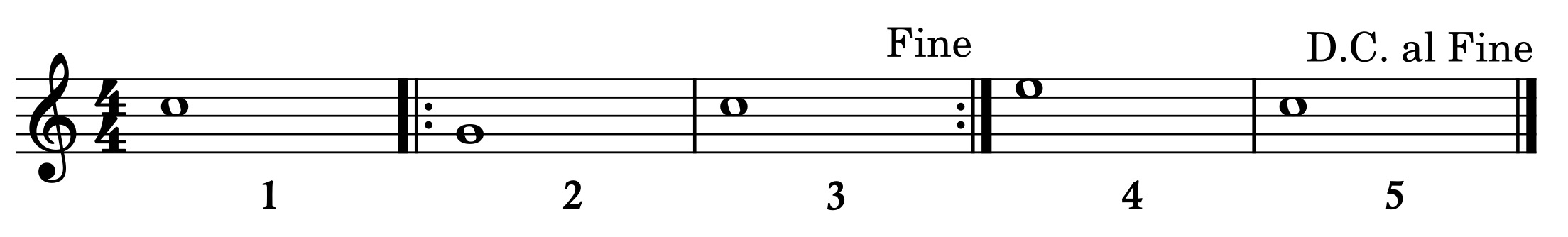

Often the first part is repeated again at the end. The expression “da capo” (D.C., again from the beginning) is usually used for this. Normally the piece ends with the word “Fine” (end); since you already encounter this word in the first run, part 2-3 is not repeated again. So in the example below you play 1-2-3-2-3-4-5-1-2-3.

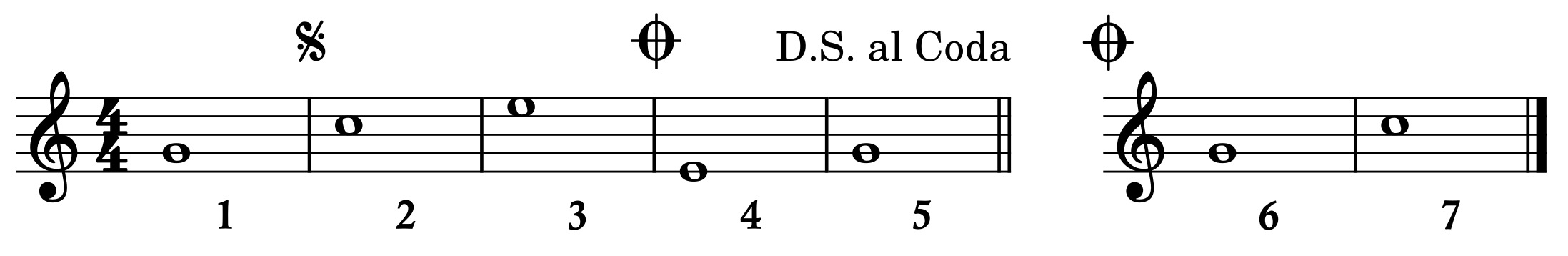

Sometimes in such situations there is also a special final part – the “coda” (tail). In the example below, the notes end in bar 5. Instead of da capo, this time “da segno” is played. The segno (sign) is the squiggly symbol at the beginning of bar 2, so from there it is played to the coda sign at the end of bar 3, and then jumps directly to bar 6. The whole sequence is therefore 1-2-3-4-5-2-3-6-7.

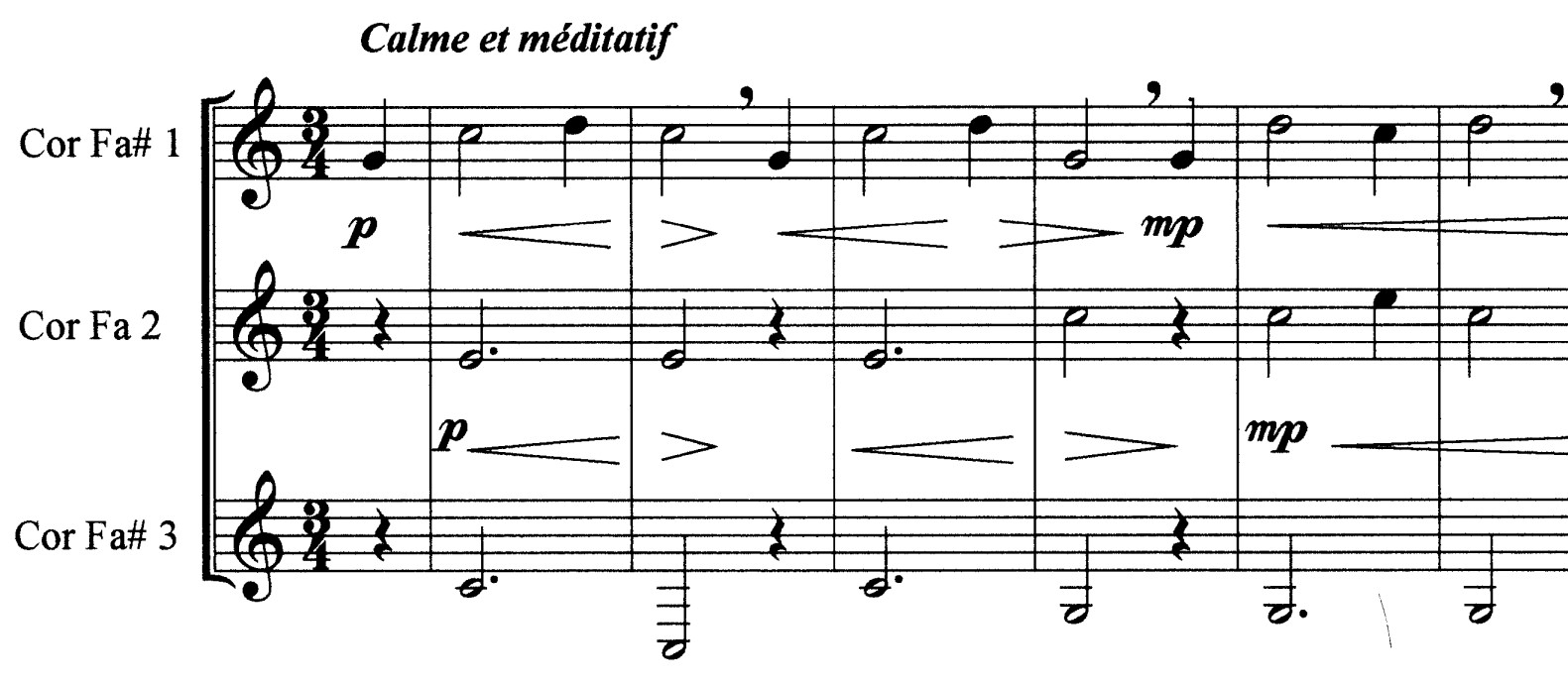

Polyphonic sheet music

When several voices play together, the staves are combined in an “accolade” (embrace). Below, as an example, the first bars of the piece Mélodie insolite by Robert Scotton. Note the square bracket on the left. The 1st voice is at the top, the 2nd and 3rd voices below. Dynamics are often omitted for the 3rd voice – it forms the bass base and is usually played mezzo forte or forte throughout. Another special feature of the piece is that two F-sharp horns (French Fa#, “fa-dièze” – where Fa means F in French, and not the alphorn-Fa) and one F horn play together.