If you have worked through lessons 1-9, there is actually nothing new to learn. On your journey with the alphorn you will keep working on the well-known topics: posture, breathing, embouchure, tongue, stamina & strength, mobility, precision, musicality. One sometimes speaks of spiral learning – you get ahead by tackling and deepening the same questions over and over again. Welcome to the spiral! Nevertheless, I would also like to give you a few new ideas along the way.

Perform In Public

Perform In Public

Playing by yourself may be a fulfilling experience. But at some point other people will inevitably listen to you – other members rehearsing in the group, your partner in the next room, hiking groups or passers-by playing outside, the video camera and the wide world recording, the jury at an alphorn competition… the audience is a new (disturbing?) element in the intimate relationship between you and your alphorn.

A lot of things that otherwise work without any problems may no longer work in front of an audience. You can’t hit the notes anymore, you can’t reach the high notes, the alphorn sounds awful, dynamics and tempo are uncontrolled. You may feel nervous and tense, have a racing heart and trouble breathing. Maybe there’s a movie running in your head where everyone is making fun of your embarrassing play. And then you lose the thread in the middle of the performance. Here are a few tips on how to overcome stage fright and how to play in front of an audience:

- Margin of safety. We usually like the newest piece in our repertoire best. You have practiced in the flow, the difficult passages work – what satisfaction! Except that with stage fright the challenging piece quickly becomes an overwhelming piece. Therefore, stay two levels below your current level during the presentation. The piece should go no more than two notes below the upper limit of your range. In a group, hide in the second voice at first. Your goal isn’t to show the audience everything you’ve got. Concentrate instead on putting your soul into the piece. Keep in mind: Playing is never difficult; it is either easy, or it is impossible (Kato Havas).

- Preparation. Before a performance, study your pieces thoroughly. Note keywords / “performance cues” in your score and internalize them during rehersals (see also the paragraph in chapter 6). This gives you a map that guides you through the performance, provides a stable grid to your interpretation and helps you to find your way back if you get lost on the way.

- Posture, breathing, lip pressure, tongue. Don’t get tense and out of breath! Before the first note, go into yourself again: adopt a relaxed posture. Breathe deeply with the diaphragm (if necessary, breathe in and out several times – let go!). Using two fingers, gently place the horn on your lips. Position the tip of your tongue behind the bottom row of teeth. Then you let the air flow into your body and breathe into your horn.

- Zen. It’s all about attitude. Do not look at yourself with a critical eye, but concentrate fully on your piece. There is no audience! Play like you practiced at home. Take your time. Allow the breaks. At the end of the piece, let the tone fade away, only in the silence do you take the alphorn from your lips.

Despite all the difficulties: the audience also gives you a lot in return. A little serenade at a birthday or a wedding, at a neighborhood party, in front of a retirement home or other event is always appreciated – as long as it doesn’t take too long (!!!). Perhaps you awaken romanticizing images? I’m always surprised how people (including young people and urban liberals) are simply happy about the alphorn and very, very, very generously ignore musical mistakes. This is especially true when playing in nature. Hikers will tell you that the sound of your alphorn carried them up the mountain. Many times, passer-bys applauded when I practiced the alphorn with complete beginners in the alps. Foreign tourists love alphorns and before you know it you’re going viral on youtube.

Büchel

Büchel

After some time with the alphorn, the Büchel (pronounced like “b-yoo-chal” or in phonetics /ˈbʏçəl/) offers itself as a natural complement. If you get into it, the first thing you’ll notice is that the Büchel demands a lot more from you than your usual instrument. An often-cited rule-of-thumb says that 10 minutes of practice on the Büchel is equivalent to about 30 minutes on the alphorn. It will probably take you a year to get a nice tone and reach the same pitch as on the alphorn. At least you can transfer everything you train on the Büchel directly to the alphorn (those who play both instruments, often train exclusively on the Büchel).

Whether C or B-flat (I find A-flat Büchel unnecessary as they sound very similar to the F-sharp alphorns), or which style you want to play, is a matter of taste. I am a big fan of the Muotathaler Gsätzli.

![]() Further information

Further information

- The “Büchelbox” by Balthasar Streiff and Yannick Wey is the new testament for Büchel players. In the two volumes available so far you will find a lot of sheet music material from different regions as well as detailed background information about Büchel, Wurzhorn, Trembita and Neverlur (albeit the texts are only available in German).

- An alternative to the Büchel is the Norwegian Neverlure. It resembles the “Stockbüchel” (a straight version of the Büchel) and is wrapped with birch bark like the original Muotathal Büchel. Depending on the tuning, the Neverlure is around 1.2m long and can be played up to about the ninth overtone. Unfortunately, the last builder of Norvegian neverlurs, Magnar Storbækken, died in 2022.

- The bugle, used as signalling instrument by armies and boy scouts, has a lot in common with the Büchel. So far, nobody has come up with an entirely convincing explanation why they share an almost identical name.

Circular Breathing and Didgeridoo

Circular Breathing and Didgeridoo

You don’t necessarily need circular breathing. And you can learn circular breathing also directly on the alphorn. However, the didgeridoo is an effective training instrument for your tongue and is simply fun to play with – perhaps also because its hippie image contrasts so nicely with the conservative alphorn.

To learn circular breathing, there are countless tutorials on youtube. I learned it via the following method:

- “Chew” the air in your mouth first. Squeeze it from one cheek to the other. While doing this, perceive the compressed air as an amorphous mass, similar to a liquid.

- Fill your mouth with water. Form the alphorn embouchure with it. Now slowly push the water through your lips with your cheeks or tongue. Repeat this process, trying to breathe in and out through your nose (it is easier to use short and flat breathing first to get the feeling).

- Put the two elements together: instead of water, now press compressed air through your lips. Buzze. While the cheek muscle or tongue pushes the air out of the mouth, breathe through the nose into the lungs – like you did with the water.

- Expand the breathing into a cycle: At some point, the cheek muscle or tongue will have pushed all the air out of the mouth. Just before that, open the valve in the throat and push the air from the lungs into the mouth. While doing this, keep the flow of compressed air through the lips – keep buzzing! This step is hard for everybody. In the beginning, the airflow breaks off briefly in each cycle. It takes about 20 hours of practice to manage the continuous air flow.

- Finally, transfer circular breathing to the instrument. From here you can go further: try to use the tongue more instead of the cheek muscles. On the didge you can learn to change the timbre and overtones by using different tongue shapes or rehearse rhythmic patterns. On the alphorn you can also practice circular breathing on different pitches.

![]() Further information

Further information

- In Bern, a scene around the pioneers Willi Grimm and Res Margot has been experimenting with the combination of alphorn and didgeridoo for quite some time; here is a video from the Klangkeller.

Multiphonics

Multiphonics

Normally, the alphorn produces one note at the time. But if you sing into the mouthpiece while playing the alphorn, exciting sounds are created. Check for “multiphonics on trumpet horn trombone” in youtube to see what’s possible – you will find plenty of examples (e.g. this). Specifically for the alphorn, in this video, Philipp Haagen uses multiphonics in a jam session; here a video with multiphonics and overtone singing by Balthasar Streiff; here my interpretation of Stille Nacht. There are also a few sheet music (e.g. the piece Rucola Rif by William Hopson, published in the collection Arioso; here my arrangement for Luegid vo Bärg und Tal). Even if you don’t like to sing into the horn in public, it’s a good exercise for sound quality.

The easiest way is to start with a fixed, relatively low note on the alphorn and sing matching overtones (e.g. play C3 or C4 and sing an E5). Try to sing into the tone of the alphorn. If the intonation is right, the two notes will blend into one full sound. Normally you will observe that the sound “wobbles”. This is called a “beat” and is due to the slight difference between the frequence of your sung tone and the corresponding harmonic of the played tone. The greater the difference in pitch, the higher the frequency of the beat. Try to slightly adjust the intonation and observe how the beat changes. It is somewhat more difficult to play a melody on the alphorn and sing a fixed note at the same time. You can also experiment with timbre by changing the shape of the tongue or singing different vowels into the horn.

The Ten Comandments

The Ten Comandments

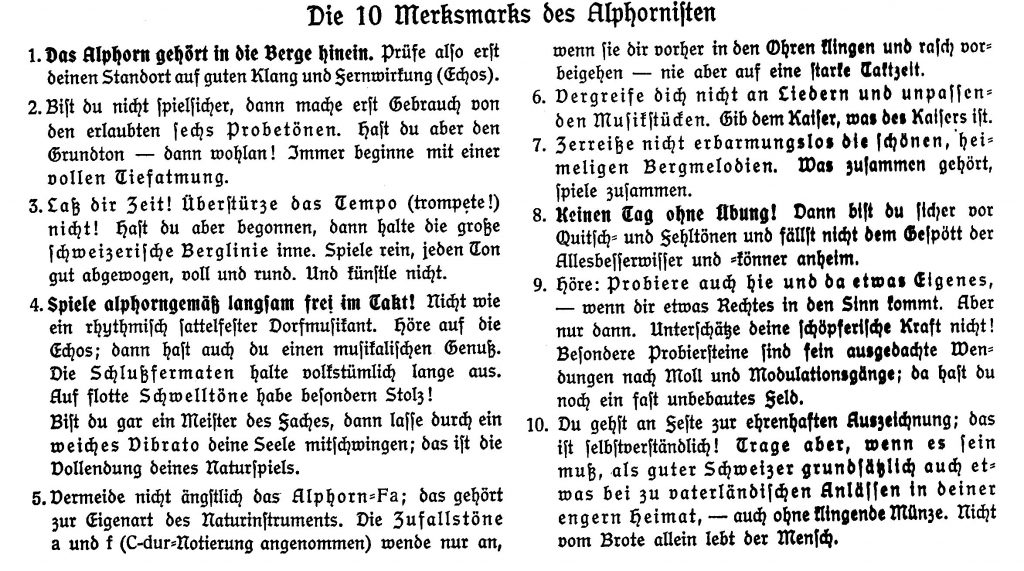

In his Alphornbüechli of 1938 (for an english translation see here), Alfred Leonz Gassmann wrote a catechism for alphorn blowers that is still readily quoted today. Here the original:

You cannot beat Gassmann in pathos! The narrative of intellectual national defense, however, has passed its sell-by date and is now quite unpalatable. Therefore, here – quasi as a conclusion to this course – my attempt at a demilitarized version:

- The alphorn follows the sound of nature and resists artificial systems. You can’t blow away the laws of physics.

- Music is free! Play on your alphorn what, how and where you like it. Don’t let the narrow minded tell you how you have to sound and look.

- Be interested in the history and tradition of your instrument. But also dare to play your own melodies!

- Stay loose and relaxed. It is not your testosterone, but your breath that makes the alphorn sound.

- Be gentle with your instrument – the alphorn is not a halberd! Don’t crush your lips or your horn will squeak like a rubber duck.

- Stand in balance and breathe deeply. When you exhale into your instrument like this, the music flows from your innermost being.

- Put your true feelings into the music. Do not drown them with false pathos.

- Practice daily with a clear goal in mind. Every moment with your instrument is precious, don’t waste it. Stay focused and fresh, that’s the only way to get into the flow.

- Go looking for echoes and reverberations – you will find them not only in the mountains. If you follow the sound of the alphorn, you will hear the world with new ears.

- Don’t be afraid of what others may think of your playing. Take the audience with you on your journey, but leave your ego behind.